So, are you a square, a cone, or a needle?

I suppose the correct response is: ‘What on earth are you talking about?’ and I guess you’d be right. It is up to me to elaborate on what I mean. But first I’ll have to explain how I came up with this question in the first place…

When you start university, the subjects, or rather sub-subjects you can specialise into are laid out before you in different ‘fields’. This is an appropriate word, considering how immense the number of choices seems. You are presented with more information and specialties than you can shake an overpriced textbook at, and it’s up to you to narrow it all down to one or two if you want to progress.

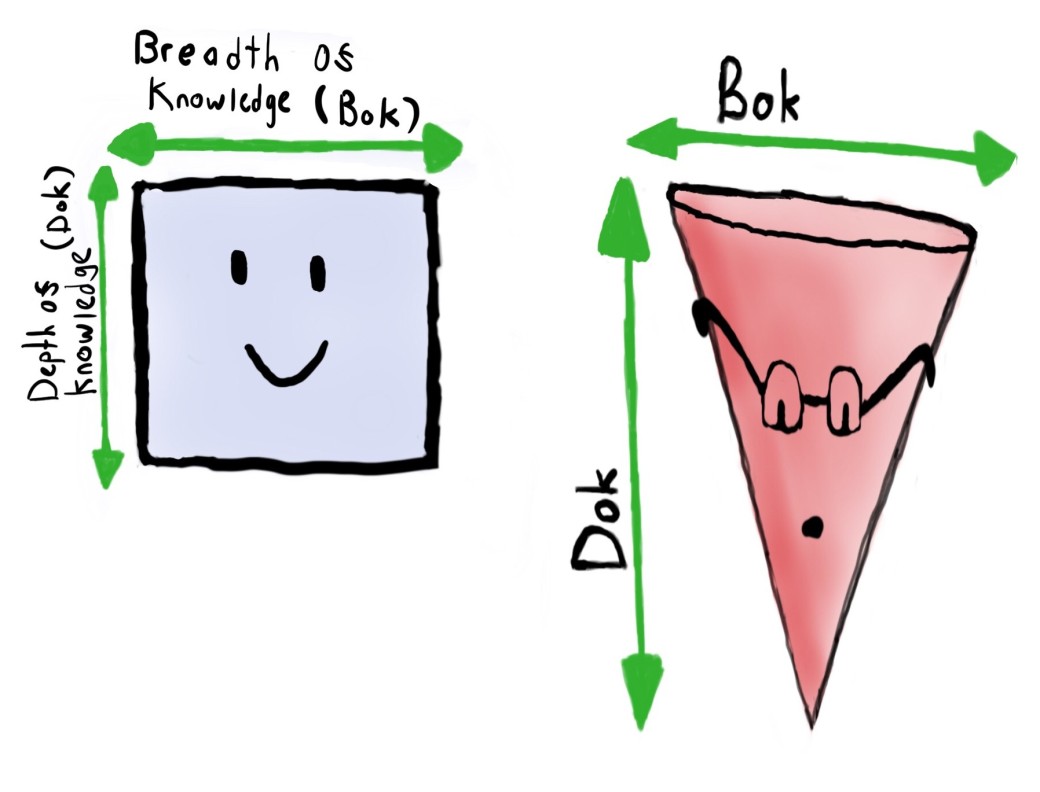

If you’d taken an overall measurement of knowledge at the start of mine and anyone else’s university education, it would probably look something like this…

-

An innocent square, unburdened by student loans, deadlines, and the thought that education must end and you have to start adulting.

I believe, in terms of knowledge breadth (how many things you know about) and knowledge depth (how much you know about said things) that most people start higher education fairly similar in both, while we may be more drawn to or naturally talented in certain areas of study, the inherent structure of A-levels or other post-school education tends to leave our knowledge bases about even across the board. But what happens after the beginning of university?

Starting a degree is the first time most people feel they are developing what I’m going to refer to as a “cone of knowledge”. A phenomenon by which you begin to specialise in one core topic, at the expense of knowledge about the surrounding ones, your square will begin to taper, and end up becoming a bit more…coney.

Symptoms include being picky over the use of the word ‘significant’ and beginning sentences with “current consensus shows…”

For example, at the end of second year, a bright-eyed and bushy-tailed me uttered the words, “Oh, Genetics looks fun, I guess I’ll choose that”. Suddenly, a class of 350 trainee scientists was pulled in different disciplinary directions, with mine whittled down to just 16. Each discipline allowed students to evolve themselves in different ways. As a budding geneticist, I occasionally worried we’d picked the educational equivalent of an evolutionary dead end.

Thankfully, me and the rest of the genetics course fell into the ‘platypus’ category of oddity, instead of, for example, the ‘dodo’ variety. The knowledge and interest I gained on genes, DNA, evolution and inheritance is most likely going to make up or be involved in a large portion of the things I talk about in the future.

So after my bachelors, having finally found a subject I felt confident and settled in, with a few months lab experience under my belt, I made the logical decision and continued in this subject area switched to a completely different field. Neuroscience.

This wasn’t a completely random decision. Like genes, brains are something I’ve always been interested in. I seem to be unstoppable drawn towards things that are irreducibly complex or complicated, or at least that’s what I tell myself while trying to untangle the wires from beneath my desk.

I had hoped, going into it, there would be some overlap between the two subjects. I knew it was possible, as my undergraduate project had involved looking at gene expression in the developing brain. But I quickly found that just because neuroscience plays by the same scientific rules, it doesn’t mean it is in anyway the same game.

Genes, as some of you may know, are small individual units of heredity made up by DNA, that tend to code for a specific protein (except when they don’t, but that’s a caveat for another time). Each one can be described as a tiny little instruction manual for one building block of an entire organism, and like tiny little instruction manuals, the directions can be difficult to read. However, science has taken great leaps in the past decade and a half in learning to decipher it.

Brains, on the other hand, pose an entirely different problem. They raise the mind boggling question of whether it is possible to understand the very thing that powers understanding. It’s the sort of thing that leads to fellow neuroscientists narrowing their eyes at each other and saying things like ‘You better not be talking about philosophy’.

To compare to genes, trying to understand the brain’s instructions may be like opening the first page and reading “To understand this manual you must have first read the manual”. It could just be something we can never achieve, due to our lack of an outsiders point of view. In other words, it feels like the darned thing won’t sit still long enough for us to work it out.

To pull this back to the shapes I’ve been mentioning, my ‘cone of knowledge’ had definitely narrowed, and was becoming more of a pointed triangle by this point. It amazed me how quickly you can put on intellectual blinkers to other subject areas when you’re in a lab environment. Sometimes it’s simply necessary to get through the volume of information on your specific topic, and I think this is why you get the occasional ‘needle’ in a lab environment.

Disclaimer: The look of horror and general scruffiness is my personal experience of a needly lifestyle, and is not indicative of the needle population at large.

A needle tends to be the one who would perfect their topic on mastermind or university challenge but shrugs on the general knowledge round in a pub quiz because they simply don’t have time for keeping up with daily events.

Don’t get me wrong, the overwhelming number of people I’ve met in science have somehow managed to hang on to their random facts and niche interests despite the sometimes frustratingly specific information they encounter. Everyone acts a bit square at times, and everyone can get a bit needley.

But science needs those needles, it needs those finely tuned points of specificity to pop the never-ending balloons of ignorance. And if you put enough of those sharp folks together, you get a figurative bed of nails, a carpet of points that together is strong enough to hold up the weight of human advancement.

I’ve now left the world of academic research, and I’ve noticed that the switch from ‘studying’ to ‘studied’ in regards to my relationship with genetics and neuroscience has unsettled me. It sounds too historic, too final. I can feel my knowledge on the subjects fading, and I think if I don’t do something about it it will become nothing but a passing interest, something for me to regurgitate a few facts about in polite conversation.

That’s the reason I set up this blog, to hopefully preserve a knowledge of science and research that I have always enjoyed and been interested in, while also presenting it in a form people can read and (in exceptional cases) enjoy.

So while I find myself trying to fix my cone, I salute to all those people who know exactly what their shape should be.

***

This entry is a bit longer than I’ll be aiming for in future weeks (although I’m aware I’m now making it longer discussing it) and this blog post began as a 200-word section for the ‘About page’. So when I try to write an actual first blog post you can expect the novel out early 2017…